Recently voices have been heard across the divide: Ta Nahesi Coates is on every media channel, DWatkins has been made an official Baltimore SUN columnist, and a bunch of experts descend on ground zero of the unrest that shook Baltimore on April 27 and the city transportation department conducts a listening session there.

But aside from those overtures, there is no denying that the area where Pennsylvania and NorthAvenues intersect is an unknown for those who live in the more prosperous parts of the city. Likewise, Guilford and Mount Washington are a world apart for residents of the communities of Upton, Druid Heights, Harlem Park or Rosemont, to name just a few. The same statement could be made for just about any American city of a certain size.

One of the insidious traits of segregation is how easy it makes it for the haves to ignore the plight of the have-nots. For most whites, concentrated poverty and its many ills are an abstraction—something they read about but rarely see, since it exists in parts of town they don't live in or work in or visit. (Steve Bogira, Chicago Reader)

In the case of the now infamous Penn-North area, it isn't that there aren't any services, there is a subway station meeting several bus lines, there is a very nice city library, the Arch Social Club and until it burned down, a CVS that is now being rebuilt. There are bail bonds offices and within a half mile some 20 to 30 small storefront operations, several of which call themselves groceries. There are even some street trees on the nearest block of Pennsylvania Avenue which looks a bit like a real main street here. On a warm and sunny fall afternoon the hustle and bustle suggests a healthy street-life, Jane Jacobs’ “eyes on the street.”

It takes a second and third look to realize it isn't all so great. The stores lack variety in their offerings and a good many of the folks on the sidewalks are selling their own goods, right under the nose of the foot patrol of the BCPD and much to the chagrin of those who operate legitimate businesses here. Parents don't want to send their kids to the library, the bail bondsman says the police just don’t do anything and the African American activist who runs the Arch Club agrees.

Wealthy suburbs benefit from a vibrant central city—it's often what attracts businesses and people to a region. But those wealthy suburbs tend not to do their share when it comes to dealing with the region's social problems, Orfield maintains. (Myron Orfield, executive director of the Institute on Race & Poverty at the University of Minnesota.)

Some at the listening session criticized MTA, observing that while their subway station is the most frequented one in the system, it is a mess. Kids turn the escalators off, somebody complains, sometimes the elevators don't run either, and maybe not even at the next station down "The Avenue" either. "At the Johns Hopkins station", somebody says, to establish contrast, "you can eat from the handrail."

The #13 bus running on North Avenue has 12,000 riders a day but it is slow, often late, comes bunched up with vehicles that should be 10 minutes earlier or later and often doesn't show up at all. The representative from MTA at the listening session makes no excuses. We know we are not performing well he admits and that, too, is a new thing in this fledgling dialogue.

The city transportation department has inserted $5 million into the capital program to fix up the Penn-North intersection and has already begun to fix broken curbs, streetlights, missing signs and what they summarily call "broken transportation infrastructure". The Baltimore Development Corporation gives out facade grants so businesses can repair or upgrade their storefronts, Blue Water Baltimore received a grant to plant hundreds of trees in empty tree pits. The paint of a huge new mural on the side of the Arch Social Club is still wet, the lower portion still incomplete – an art grant is at work here.

|

| Not a lucky bus: The #13 on North Avenue Photo: ArchPlan |

When a Rite Aid store reopened recently, also closed by riot damage, the Mayor, Congressman, State senator and City Council were present to welcome the occasion. The World Bank even came to the area to visit the local community development corporation and listened to an eight year old describe his view of things.

The uprising has certainly brought attention and action such as the long-deferred maintenance of the public works department. Like Watts in L.A. and Ferguson near St. Louis, unrest will shake things up for a while until everybody falls back into the default mode.

When the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968, it barred the outright racial discrimination that was then routine. It also required the government to go one step further — to actively dismantle segregation and foster integration in its place — a mandate that for decades has been largely forgotten, neglected and unenforced.(Emily Badger, Wonkblog, Washington Post)

Will the new attention be enough to stave off another uprising? The answer will likely depend more on the outcome of the Freddie Grey trial against the police officers than on freshly planted tree saplings. The outlook across the country is rather bleak.

As America has grown more unequal and divided, its cities and metro areas have become even more so. New York’s level of inequality is comparable to Swaziland's, L.A.’s to the Dominican Republic's, Chicago's to El Salvador's, and Seattle's to Nigeria's.(Richard Florida)

It takes a longer-term view and a bigger haul to address longstanding structural issues at play in Penn-North. To this end experts convened by the local Urban Land Institute(ULI), which in turn was brought in by Baltimore's mayor to reinvigorate several commercial corridors in poor neighborhoods as part of the LINCS neighborhood corridor initiative scouted out the area for two full days. They interviewed everybody that anybody considered a "stakeholder". The ones who have a daily and seemingly permanent stake in the ground of the public spaces – the homeless and the drug dealers – they were not invited.

The hypersegregated black neighborhoods continue to lead the city in the same wretched problems as in the 60s. In some ways, things are worse. There's not just a lack of legitimate jobs in these areas today, but also a surplus of people without skills—and more of them have criminal records now as well, from the war on drugs. Predatory lending has multiplied the number of abandoned buildings in these neighborhoods. (Steve Bogira, Chicago Reader)

However exhaustive the listening sessions, however experienced the experts, they can't conceal the fact that the area "has no market", which in a society that runs on profit means gloom and doom. Without investors who are ready to fill the many vacant lots, open the much desired sit-down restaurants, build market rate housing to bring purchase power into the area that can support a real grocery store the only entity infusing dollars is the government and its actions are not always helpful although one can point to some successes: The city which had put a lot of effort into getting a Target and various other anchor stores to establish a presence at Mondawmin Mall not even half a mile up the street. "After you put the Target in, even white people went there" somebody observed. The reality is more like this: A lot of poor people can still generate high sales and revenues. The word in the community is that the Mondawmin mall is one of the highest grossing malls in the country.

In a twist of irony, though, the refurbished mall makes it not only harder for merchants to take root at Penn and North, the mall was also the place where the unrest and looting started. To add insult to injury, the worst of the burning and smashing did not unfold at the mall where there are national chains, but instead was saved for the stores owned by individual proprietors at Penn North and points east and south. It was only when the rioters reached the Inner Harbor that police took real action to defend property, another symptom of a divided city where the rules are not the same across the entire town just as they aren't anywhere else in the US.

|

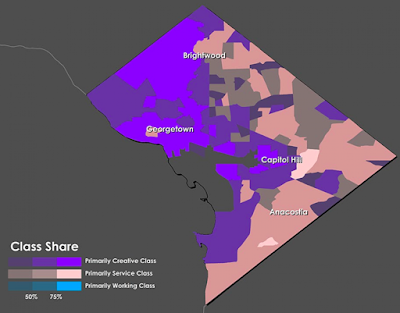

| "The Divided City: and the Shape of the New Metropolis," R. Florida, Z. Matheson, P. Adler, T. Brydges |

One can debate whether there ever was a time when cities were not divided, here in the US or anywhere in the world, really. The homeless, the disinvested areas and poverty in cities contrast with glitz in many places, even in a place like Switzerland that has far greater economic equality on a macro level. But it is a matter of degree. It is in Baltimore and a few other former industrial centers that the poverty rates reach a staggering 25%, that life expectancy rates vary by more than 20 years over just a handful of miles and that incarceration rates, unemployment and lack of education is so rampant among young men of color. And maybe it isn't a coincidence that racially restrictive zoning that codified the exclusion of residents of color in certain neighborhoods originated here as well. The arsenal of exclusion has an ammunition depot here as authors Antero Pietela and Dan D'Oca illustrate in their respective books, "Not in my Neighborhood" and "The Arsenal of Exclusion". (D'Oca lectured about this on on North Avenue the same evening the Penn North expert group reported their findings).

Baltimore was once to the invisible wall building industry what Detroit was to the automotive industry—an innovative workshop where creative minds worked to think up, invent, test out, and ultimately export methods of exclusion.(Dan D'Oca)

Exclusion by design today is not as explicit as it used to be but it continues to exist, at times in a sublime and non intentional way. The economics of homeowner tax credits, the way real estate can be written off, the way how Medicare is based on a calculation of the cost of living that is currently heavily influenced by gasoline prices, no matter if someone actually has a car, there are many obvious and hidden reasons why the American city not only has remained divided over decades but has become even more so in recent years.

|

| There is now dialogue where there was silence Listening and planning session with the head of the Baltimore Development Corporation |

"Segregation didn't happen by accident, and integration doesn't happen by accident, [...] It can be done, but you really have to plan to do it. You have to make it a goal." (Gary Orfield, Co-director of the Civil Rights Project at UCLA)

The new desire to communicate and act across the divide is welcome in light of the urgency of reducing these divisions should we not risk to have the entire powder keg blow up. As such, Baltimore's Penn North is nothing but a microcosm of the divided American city and increasingly of a divided world in which millions have taken to unprecedented migrations in the search of better opportunities. It is up to this country, long the quintessential global symbol of opportunity, to fulfill this promise inside its own cities.

This is a pivotal moment: Just when our cities and urban areas have started to revive and re-urbanize, they are faced with growing class divisions that threaten their development in new and even more vexing ways. (Richard Florida)

Klaus Philipsen, FAIAedited by Ben Groff, JD

How the creative class is dividing the American City (Washington Post)

How railroads, highways and other man-made lines racially divide America’s cities (Washington Post)

Separate, Unequal, and Ignored (Chicago Reader)

The Divided City (CityLab)

25 Most Segregated Cities in America (Business Insider)

The life expectancy gap grows wider (NY Times)

The life expectancy gap grows wider (NY Times)

No comments:

Post a Comment